When Best Film of All-Time lists are compiled (which is actually pretty often. People seem to love a good list) there's always the usual suspects that seem to get the top spot. Usually it's some combination of Casablanca, The Godfather, Gone With the Wind, or sure-thing and (almost) undisputed champ, Citizen Kane. And you'll get no complaints from me regarding any of those films topping any best of list (although, let's be honest - The Godfather Part II is better than the first). But it's always interesting when an unexpected (but no less deserving film) gets that number one spot.

A couple of years ago when Sight and Sound released it's once-a-decade list (their list is pretty much considered the gold standard when it comes to lists of this sort), there was a little bit of a shock when it was revealed that Vertigo had overtaken Citizen Kane for the coveted top ranking. And in my research for this month's Blind Spot (courtesy of Roger Ebert), I was more surprised to find that a list from London's Spectator chose not Kane, Vertigo, or The Godfather for the top honor but the odd-ball choice of The Night of the Hunter. The only film directed by actor Charles Laughton, it was actually a critical and commercial disappoint at the time of its release. Amazingly not even nominated for a single Oscar nomination the year of its release, its esteem has only risen over the years. After hearing about it for years, I finally caught up with this twisted little film this past weekend for my entry in this month's Blind Spot.

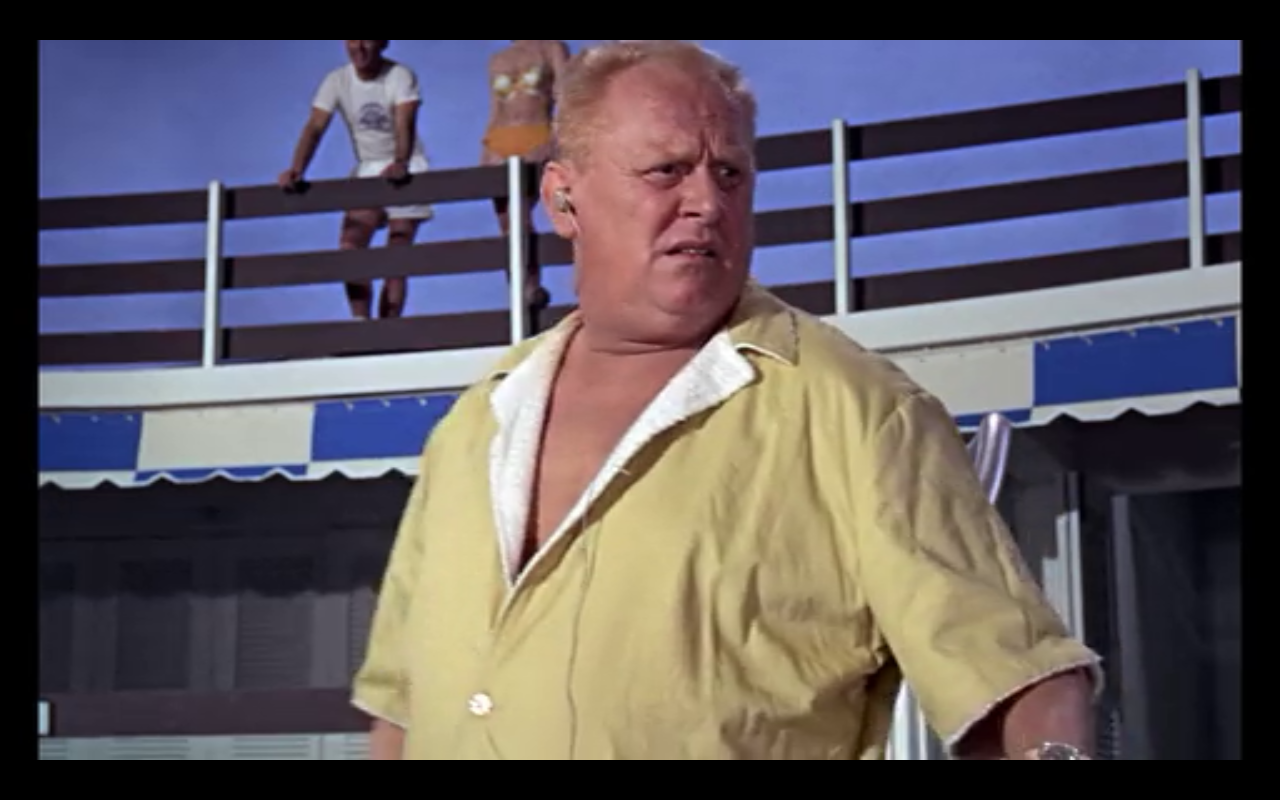

The film stars Robert Mitchum as on of the creepiest characters to ever grace the screen, Reverend Harry Powell. A corrupt preacher (although, he never can give a straight answer as to what religion he's actually associated with) that has conversations with god and preys on unsuspecting widows, robbing them of their money and their lives. Powell is clearly a misogynist with a strong distaste for anything involving femininity and sexuality. In one of the first scenes we see of Powell, he sits at a burlesque show, getting so worked up with disgust that he cuts through his pocket with his ever-ready switchblade. Which doesn't bode well for the latest wife to cross his path, Shelley Winters.

Winters is Willa Harper, a mother of two and a recent widow after her husband, Ben Harper, (no, not Laura Dern's ex-husband, Ben Harper. Although, I can see some Shelley Winters in Dern... ) is hanged after stealing $10,000 and killing two men during the robbery. Powell, after sharing a cell with Harper, sees the encounter as a sign from god and marries Willa to recover the fortune. Things don't go quite as Willa had envisioned (won't the hot, creepy guy make a fantastic stepfather?!?), especially during the night of their wedding in which she receives a brutal, verbal dressing-down from Powell that's as uncomfortable for the viewer as it is for the attacked Willa. (But, I mean, she had to have suspected things weren't gonna work out well when she finds his beloved switchblade in the pocket of his coat before she tries to hop into bed with him. Her reaction at its discovery - with a shrug and the bless-his-heart delivery of "Men..." - is comedic genius and sets us off-balance for the tense scene that follows.)

Ah, little lad, you're staring at my fingers. Would you like me to tell you the little story of right-hand/left-hand? The story of good and evil? H-A-T-E! It was with this left hand that old brother Cain struck the blow that laid his brother low. L-O-V-E! You see these fingers, dear hearts? These fingers has veins that run straight to the soul of man. The right hand, friends, the hand of love. Now watch, and I'll show you the story of life. Those fingers, dear hearts, is always a-warring and a-tugging, one agin t'other. Now watch 'em! Old brother left hand, left hand he's a fighting, and it looks like love's a goner. But wait a minute! Hot dog, love's a winning! Yessirree! It's love that's won, and old left hand hate is down for the count!After such a lovely story, is it a surprise that John doesn't trust the shady preacher? And once Powell murders Willa (in one of the film's most arresting images we see a watery vision of her in her car at the bottom of the river, her hair mingling with the seaweed as she transforms into some sort of water nymph in her liquid tomb), John and his little sister Pearl (her doll is the stolen money's hiding spot) escape the clutches of the murderous Powell and take off down the river in a nightmarish, biblical journey. The montage is filled with images of fantastical spiderwebs and frogs, emphasizing the dark fairy tale quality that the film emulates.

The children are taken in by a kindly woman named Rachel Cooper (played by silent film star, Lillian Gish) who protects them from the omnipresent Powell. And the two face off in a battle of good and evil, mirroring the dichotomy of love and hate that Powell is so found of. Gish's Rachel, an angel with a shotgun, is not afraid of the demonic Powell. And even if good doesn't entirely win out in the end, it puts up a good fight against the evil's of Mitchum's Reverend. And an open-ended conclusion leaves us with an uneasy feeling of history repeating.